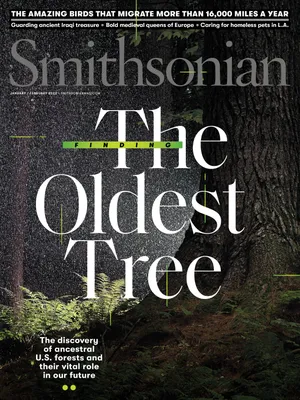

What Animal Can Run The Longest Distance Without Stopping

Photographs by Melissa Groo

Bog walking is a treacherous business concern. The bog, or muskeg, nearly Beluga, Alaska, is a floating mass of vegetation, grassy hummocks and stunted black spruce trees that stretch for miles in every direction, with the snow-flecked mountains of the Alaska Range shining in the distance. Few trails be. Walking here is like sloshing across a very wet sponge, as each step sinks into a few inches of h2o. Information technology feels as if the basis might give way. Sometimes information technology does. A incorrect footstep tin can sink the uninitiated into thigh-deep h2o that requires a hand upwards. Clouds of mosquitoes search for whatsoever bit of exposed flesh. Rangy moose emerge from groves of dwarf trees to threaten trespassers.

This, however, is where one of the earth's premier ultra-endurance athletes lives.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/55/6e/556ee214-92c1-4496-b730-a10e282eb72e/janfeb2022_d07_migratorybirds.jpg)

Long-distance migration is the most farthermost and life-threatening affair that any animal does. And migratory shorebirds make the most miraculous journeys of all, given the distances they cover and their tiny size. There are some seventy species of shorebirds in the earth that make the journeying from the superlative of the earth to the lesser and back every year.

The Hudsonian godwit is one of them. Named after the Canadian bay where the species was first identified, and the bird's distinctive two-syllable cry ("god-wiiit!"), Hudsonian godwits lay their eggs each spring in this Alaskan bog. (All godwits breed in the Northern Hemisphere.) In June or July, they leave their self-sufficient hatchlings and head south. First, they fly for iii days to the wetlands of Saskatchewan and feed for one month. Then they go on down through the Americas to the northern Amazon—a iv,000-mile trip. They feed over again and a week afterwards head to Argentina, feeding some other time earlier continuing over the Andes to Chiloé Island, on the fecund Gulf of Ancud, where they get in in September or October and winter for a little over six months.

The longest leg of their journeying, some six,000 miles, is on the return from Chile. They wing night and twenty-four hour period at speeds between 29 and 50 miles per hour, non stopping to eat, beverage or rest. They pause for a couple of weeks to refuel in wetlands in the central U.s.a.—normally Nebraska, S Dakota, Kansas or Oklahoma—and then continue back to the Alaskan bog. Their goal is an endless summertime.

In person, the Hudsonian godwit is prepossessing, sleek and reddish brown and gold in its Alaskan spring breeding colors, with slender stiltlike legs and a very long, upturned pecker especially designed for feeding in mud. If you are a researcher trying to capture and written report baby Hudsonian godwits, you'll wait for a well-camouflaged, soup-cup-size nest on the ground. One time you find it, you'll go close enough to the mother bird to scare her into flight.

That'due south why Nathan Senner, an assistant professor of ornithology at the Academy of S Carolina, is patiently and doggedly slogging through this swamp, clad in army-green hip boots. He'due south accompanied by his wife and fellow ornithologist, Maria Stager, and master's pupil Lauren Puleo. They are waiting for the elegant, long-legged, long-billed mother bird to fly upward, shrieking and scold-ing, leaving its four—near always iv—moss-brownish eggs exposed.

"What attracted me to them was this mystery that I knew something nearly and could assistance out with."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b0/fa/b0fa8e97-d974-4291-b243-dba425ab18b2/janfeb2022_d18_migratorybirds.jpg)

A problem with this tactic is that some females are so difficult-wired to protect their brood, they won't fly abroad from the nest entirely, even when you're close enough to stride on them.

"So the holy grail for finding a nest is the incubation switch," Senner explains. That happens when the male returns home from a day feeding on mollusks and marine worms on the vast shimmering mud flats in the nearby Gulf of Alaska. The researchers spot him as he zooms in to take over nest duties so the female person can feed. "You come across the male go to the ground and the female popular upwards. And, aha, there's the nest."

Tromping through the bog last spring, Senner and his squad plant xv nests. No small feat: It takes 24 person hours of searching in the perpetual twilight of belatedly spring in Alaska to find just one. When a nest is constitute, Senner picks upwards and floats each egg in a small articulate plastic cup filled with water. In one instance, an aroused mother godwit casts an agitated eye from the meridian of a nearby stunted tree and swoop bombs the research coiffure to defend her nest. Senner nonchalantly ducks the angry bird and continues his piece of work. The summit and angle of the floating egg indicates when the chicks volition hatch: His goal is to come back and detect the babies within hours after they've pecked their way out of their shells.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c1/8e/c18e8c11-e94c-4bb4-a525-39bad83a0329/janfeb2022_d19_migratorybirds.jpg)

Robins, bluebirds, hummingbirds and many other birds are altricial. That means they are helpless at nativity, featherless, eyes airtight and nest-bound, and they need parental care before they learn to fly. Godwits and virtually other ground nesters, on the other hand, are precocial birds. The hatchlings are raring to go a couple of hours later they emerge, running across the bog snapping at swarms of mosquitoes and flies. This firsthand cocky-sufficiency also helps them avoid being gobbled upward in the nest by a voracious mew gull or a trick. Either manner, after those first few hours, they'll be hard to detect and therefore lost to the crusade of inquiry. Senner isn't worried. "I accept literally never missed a hatch," he says.

A newly hatched Hudsonian godwit weighs less than 1 ounce, though before it sets off on its journey to the other end of the world, it bulks itself upward to more than 12 times that weight. Scientists who study these birds readily confess to not knowing many important facts about them—from where some of them finish over to how they use magnetic forces, how they read weather systems and, in general, how the hell they can maybe do what they practise. Answers to initial questions often spawn a flock of more vexing ones.

A big reason Senner comes hither in the spring is to suss out the forces that are driving down the numbers of Hudsonian godwits and other migratory shorebird species. In 2018, he and John W. Fitzpatrick, the recently retired executive managing director of one of the world's leading bird research institutions, the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, co-authored a New York Times op-ed about migratory shorebirds that ended, "Numbers of some species are falling and so apace that many biologists fright an imminent planet-broad moving ridge of extinctions." This free fall—which Senner and Fitzpatrick call the "number one conservation crisis facing birds"—is why far-flung teams of researchers around the globe are striving with more than urgency than ever to unravel the myriad mysteries of migratory shorebirds.

Senner has been immersed in the globe of migratory shorebirds almost all of his life. "I grew up with godwits," he says. He was a serious birdwatcher as a youngster, hiking with his parents on a coastal trail nearly his Anchorange abode, where godwits were a mutual sight. His father, Stanley, was the executive manager of the Audubon state office in Alaska, and was part of the scientific team that responded to the Exxon Valdez oil spill in 1989. Young Nate grew up with avian flashcards and dinner conversations almost the challenge of protecting birds.

Another of Senner's passions has further cemented his kinship with these migrants: He runs marathons, which gives him fifty-fifty more respect for the marathoners of the bird world. (His best time is an impressive two:29.10.)

Senner is 40 and whip-thin, with a ready smiling and a wealth of bird knowledge in his head. As an undergraduate at Carleton College, he worked on shorebird biological science with the United states of america Geological Survey (USGS) in Alaska. He earned his PhD at Cornell and worked as a postdoc at the Global Flyway Network with famed Dutch researcher Theunis Piersma at the University of Groningen.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/de/89/de894c2c-cea5-4dd8-84f6-7fa4c1478eb0/janfeb2022_d15_migratorybirds.jpg)

Because he grew up in Anchorage with Hudsonian godwits right outside his dorsum door, Senner says he never thought too much about them until he learned that "most people idea godwits were actually special, super mysterious and 1 of the rarest birds in North America, because they had never seen 1. They came to Alaska to come across them. And and then what attracted me to them was this mystery that I knew something about and could help out with." He became more curious, too, about where the godwits went when they left.

After he earned his undergraduate caste, he was awarded a Thomas J. Watson fellowship, which funds recent graduates to travel the earth to follow their passions. He went to Brazil, Peru and elsewhere in S America to see what he could find out near godwit migration. The tracking engineering science was nonetheless in its early stages and so, but before long, he says, there was "an explosion of engineering science that immune us to blow the doors off all of these questions which we had no thought virtually."

A breakthrough in miniature tracking technology allowed researchers to see precisely where migratory birds went on their journeys. This was no small revelation. Where birds went when they left 1 place and returned months later was for centuries a confounding enigma. While some cultures, such every bit the ancient sea-going Polynesians, had knowledge of seasonal bird routes, most of the world was in the dark.

Some people speculated birds hibernated rather than migrated. One 16th-century Swedish bishop, Olaus Magnus, hypothesized birds sank into the mud at the bottom of lakes or rivers, rising to the surface at the onset of spring. 1 17th-century scientist, Charles Morton, believed the birds made a lunar landing. "Whither should these creatures go," he wrote, "unless information technology were to the moon."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/84/55/84550f5d-d6e8-47d3-8203-7769b92b96c5/janfeb2022_d11_migratorybirds.jpg)

It wasn't until the 18th century that experts began to realize that some birds were traveling to warmer climes where food was more than abundant. That fact was driven home dramatically in 1822 when a hunter in Germany downed a white stork and discovered it had been impaled by an African spear—it had flown, wounded, some two,000 miles from Africa to Europe. The Germans called it a pfeilstorch, or arrow-stork, and remarkably, 24 more pfeilstorchs accept been found in Europe in the years since.

Bird banding became the first method of shedding light on the migration mystery. In the early 1800s, John James Audubon found that birds he banded with strings tied to their legs returned to their nest the following yr. The first banding for scientific research is credited to the Smithsonian researcher Paul Bartsch, who in 1902 placed metal bands on the legs of 23 black-crowned night herons with a serial number and a message—"Return to Smithsonian Establishment."

In 1909, the American Bird Banding Association assumed oversight of all banding efforts, until, in 1920, the federal Bureau of Biological Survey created the Section of Distribution and Migration of Birds. A researcher there named Frederick C. Lincoln created the modern science of bird tracking, improving banding methods as well every bit recordkeeping, and used the information to advocate for the conservation of migratory birds.

Biologists once thought the Hudsonian godwit was 1 of the rarest species in North America, because virtually of its convenance grounds were in remote parts of Northern Canada. In the 1980s, researchers started seeing Hudsonian godwits that had been banded in Canada showing upwards in Argentina. Other godwits, without bands, were also showing upward in Republic of chile—every bit it turned out, those were the ones migrating from Alaska. It was however a mystery where they'd been in betwixt.

In 1989, the science of bird tracking took a quantum leap when albatrosses became the outset birds to be fixed with satellite tracking telemetry devices. A few years afterward, in 1994, USDA Wood Service biologist Brian Woodbridge placed a tracking device the weight of a argent dollar on two Swainson'south hawks in Butte Valley, California. A growing number of the birds weren't returning from their winter migration and the biologist was concerned. He'd known for years that these insect-eating "grasshopper hawks" went somewhere on the pampas of Argentine republic in the winter, but not precisely where. When he and his colleagues used GPS tags to detect the birds' precise location in Argentine republic, they were shocked to get in and find hundreds, and then thousands, of Swainson's hawks dead on the ground in an agricultural surface area. The birds had fed on grasshoppers that were existence sprayed with a strong pesticide chosen monocrotophos, and it was killing them, most instantly. The knowledge gained through tracking led to an international outcry. Fortunately, the Argentine government took action and the number of Swainson'south hawks recovered.

In 2007, Senner was intrigued past a study in which a team led past his mentor, USGS researcher Robert Gill, fastened satellite transmitters to xvi bar-tailed godwits in New Zealand. The birds had flown 6,300 miles from New Zealand to the Yellow Body of water, to feed on a massive mud flat at that place. Later on six weeks they'd continued on, flying 4,500 miles to southwestern Alaska to brood. The big surprise, though, had come up at the end of the breeding flavour.

Parting from the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta in western Alaska, a bird dubbed E-seven had landed more than than a week subsequently on a beach on the north isle of New Zealand—without ever stopping to residue. Information technology was the longest known nonstop migration of a land bird: eight days in the air, covering seven,250 miles. (This bird'due south distance has since been bested. The current record, ready in September 2021, belongs to a bar-tailed godwit that spent more than 11 days in the air, covering 8,100 miles.)

In 2008, Senner attached something called a geo-locator to the leg of a Hudsonian godwit in Manitoba, home to another population of Hudsonian godwits. Geo-locators are less precise than GPS transmitters, only they're cheaper, and especially minor and calorie-free. They record sunrises and sunsets as the bird flies, storing information that reveals, upon its return, where exactly information technology traveled.

In 2009, in a fundamental Canadian bog nearly Churchill, Manitoba, Senner fetched the tiny tracking device that the Hudsonian godwit had been wearing. As he took the device off the bird's leg, he wondered excitedly how far afield his subjects had traveled. "My hands were shaking so terribly," he said. "I ran back to the inquiry station and hooked it up to my computer."

"Marathoning is an inadequate metaphor for them. It's more accurate to say they have a superpower ."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/96/62/966264f0-3c94-4957-91ac-47b755215da3/janfeb2022_d99_migratorybirds.jpg)

It was a eureka moment: He learned the bird had departed its winter range in Tierra del Fuego and flown some six,000 nonstop miles until it reached the declension of Texas, its first pit cease on the style back to Churchill. This earned the Hudsonian godwit the silvery medal for nonstop long-distance flying, just backside the bar-tailed godwit. It turned out at that place was a good reason that godwits showed up in far-flung parts of the globe and not in between: They could fly day and dark, covering the entirety of Latin America without ever needing to land.

The suite of skills involved in this feat still astonishes Theunis Piersma, Senner'due south former mentor at the University of Groningen. Piersma is an expert in the "endurance physiology" that enables shorebirds to execute these migrations. "Information technology'due south difficult to selection one thing out because there is this enormous list that is totally astonishing," says Piersma.

On a Zoom call, he ticks off a few items from the list of things a migrating bird has to main: "Distance, time-keeping, navigation, predicting weather, flying at loftier altitudes, social communication and all of the physiological challenges." He adds, "Mammals are not the biggest evolutionary success. Birds are better in everything."

There is a bit of an argument most whether Arctic terns make more than impressive migrations than godwits because they fly as far as 25,000 miles round trip, from the Antarctic to the loftier Chill. When I bring this up to Senner, he dismisses information technology with a wave of his paw. "Nosotros are always duking information technology out with those tern people," he jokes. The difference is that though the tern flies farther overall, it doesn't complete such long nonstop stretches. It feeds forth the manner, so it doesn't need to go through the preflight transformations that the Hudsonian and bar-tailed godwits, and other long-distance migrants, do.

The virtually critical grooming the godwits make is packing on fat. They do this over a couple of months of avid on worms, dime-size clams and a variety of other tasty things. The added fatty doesn't negatively touch on their operation—it enables it.

Christopher Guglielmo studies endurance physiology at the University of Western Ontario. One of his papers is titled "Obese super athletes: fat-fueled migration in birds and bats." Guglielmo explains that birds evolved a system to use fat directly—instead of just using sugars or carbohydrates. They burn that fat load upward to ten times as efficiently equally humans practise. This may be the single almost important key to their migration success. Oddly, the fatty they store in accelerate also keeps them hydrated. "A marathon runner can grab a cup of h2o from the sidelines," Guglielmo says. "Birds don't take that ability. So when they fire fatty they brand carbon dioxide and water. Information technology'due south called metabolic water. So their fatty stores are acting as their bottle." He adds, "Marathoning is an inadequate metaphor for them. They can't hit the wall similar marathoners practice or they'll dice. They don't beverage for over a week. It's more accurate to say they have a superpower."

Contempo findings also defy the models that researchers have long relied on for the energetic cost of flying to birds, forcing scientists back to the drawing board. "Our models of bird flight say birds should conk out after 3 to 4.v days," Guglielmo says. "I am at a loss to explain how they do information technology for a week or more."

Unpacking the superpowers of these birds may someday atomic number 82 to medical breakthroughs for humans. "Understanding how they handle their fat has lots of implications," says Guglielmo. "Birds look like a Type 2 diabetic. A typical bird has blood sugar concentrations that are way up in the diabetic range. Yet we don't come across any of the diabetic side effects."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/e0/0e/e00ecfbe-4bfe-40e5-90cf-4b9a9e4d86dd/janfeb2022_d14_migratorybirds.jpg)

There are other adventures in avian plasticity as godwits prepare for difference. Research suggests that bar-tailed godwits double or triple the size of their pectoral muscles, their heart and their lungs alee of migration to better power their flight. To compensate, they compress their gizzards, livers, guts and kidneys. Later on they arrive at their destination, their bodies readjust. Equally they head north to brood, the testes of red knot sandpipers grow to 30 times their winter size to supply ample testosterone for singing and other fun things. Some birds grow new neurons ahead of their journeys to supplement the hippocampus, which helps with navigation.

Other adaptations include extremely aerodynamic wings and bodies. Migratory birds sleep while they fly, getting close-eye on one side of the brain while the other side stays awake and alert, so switching sides, something called uni-hemispheric slow wave sleep. Dolphins and whales sleep this way likewise.

Migratory birds besides have extremely efficient respiratory systems, much more so than other animals, which is a good thing considering they are often flying at altitudes where there is one-half every bit much oxygen equally at sea level. Before migration, bar-tailed godwits soup upward their circulatory system by increasing the number of red blood cells so they tin accept more oxygen out of each breath. They store air after it passes through their lungs and so exhale it over again.

Among the nigh remarkable adaptations are the way-finding abilities of migratory birds. Godwits don't just point themselves south with a compass and accept off for New Zealand or Chile. They navigate nimbly across the vastness and vagaries of the Pacific and the Americas. They have a very sophisticated understanding of what lies alee, and how best to handle it, from low-force per unit area systems to wind regimes and rain. "They brand adjustments we would have a difficult time doing with all of our information," said Piersma. "They play with the winds in very strategic ways. They know weather systems and they sympathise them. It's simply incredible."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/71/3b/713be98e-6847-4903-b058-4d02153976ab/janfeb2022_d01_migratorybirds.jpg)

In that location are numerous tools birds use to migrate—the stars, landforms, smells—but even calculation all of these together seems to get at only a part of the story. Researchers are still looking for a more complete explanation. A magnetic sense has long been known to play a role, but the mechanism hasn't been proven. 1 idea holds that there are magnetite crystals in the birds' cells or their beak that respond to the earth's magnetism, gently guiding them on course. Or perhaps magnetic forces tug at magnetite in the inner ears of the animals. Another leading hypothesis these days is that bird vision is continued to magnetic lines on the earth's surface involving an abstruse process called "quantum entanglement"—a phenomenon of physics that Einstein once called "spooky action at a distance."

Piersma shrugs on the Zoom call when I ask him what the mechanism is. "What is undeniable is that without a strong magnetic sense you lot just can't explicate a lot of the navigation performance," he says. "When we follow them with trackers we very often feel as if they have a GPS on board and have the same geographic cognition nosotros have."

One of the leading questions in the bird world is how they might communicate among themselves, and the function of the information they share during migration. While just a quarter of immature birds survive the mortiferous gantlet of the Alaskan bog, some 90 percentage of adults survive the slings and arrows of their southward migration. That may be considering birds that travel in groups form a collective intelligence, a grouping mind that makes far better decisions than a solitary bird.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/31/7c/317c23ec-0a82-4209-ad74-b76364eaa982/janfeb2022_d12_migratorybirds.jpg)

Migratory shorebirds are not merely equipped with highly evolved adaptations for flight and migration; their beaks are sophisticated instruments, too, with an upper bill whose end can flex up independently from the rest of the pecker to catch squirming critters. Tiny sensors, called Herbst corpuscles, cluster at the tips of their beaks. These pressure level sensors seem to enable a kind of tactile echolocation: With their beaks plunged deep into the mud and sand, the shorebirds can sense the motility of prey.

Then there is the why of migration. Every bit they pursue their eternal summer, the long periods of daylight allow the birds to enjoy more hours of feeding. They also return to the northward because loftier latitudes are extremely rich in foods that shorebirds dear. In the Bohai Bay of northern China, for instance, a disquisitional migratory shorebird stopover, there are some 50,000 precious stone clams in ane square meter of mud. In the Arctic regions, there'southward an affluence of insects for the young ones when they hatch.

A few weeks before the summer solstice, under a nickel-grayness Alaskan sky, Senner makes his nest rounds and finds that the mossy brownish, spotted egg shells are existence "starred"—the chick is ready to go and its sturdy pecker is creating an asterisk-like crack. He holds the egg to his ear and hears a slight tapping.

The adjacent day the impatient babies are pipping, or starting to break through the shell. Senner is getting excited. "Tonight," he says. "Peradventure tomorrow."

The hatching arrives afterwards than predicted, almost 2 days late. It'south the first time he's been hither since 2009, Senner says, that none of the eggs has hatched by June i. Finally, i morning a few days later, his daily rounds observe the chicks are starting to hatch. The featherlike, mottled babies are whistling away. His tape remains intact: He has still not missed a hatch.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/78/6a/786aac42-a545-4427-984e-ba2a6326a162/janfeb2022_d17_migratorybirds.jpg)

At the kickoff nest, he sits downwards and scoops the chicks upward, cradling them in his hands and briskly going nearly his research as the trigger-happy mother godwit alarms from higher up. Puleo, the graduate student, assists him. He draws a tiny drop of blood, weighs them, measures the leg, caput and bill size of each, and places a minuscule VHF radio transmitter on the fluffy back of half the chicks to follow them around the bog. He'll recapture them once a week for the first four weeks to empathise more almost their habits and bloodshed. The transmitters will autumn off before the chicks brand their first migration. Every chick also gets a small plastic tag on its tiny matchstick bird legs.

The procedures finished, Senner heads to the next nest. He says the godwit parents always return to the nest later on his measurements and rearing resumes as usual.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/98/92/9892d0f0-ee4f-46ad-93e7-3cb666933aa3/janfeb2022_d06_migratorybirds.jpg)

"Birds aren't falling out of the heaven," says Senner, "And so what is information technology? I think the bug are compounding ."

The adult godwits exit here in June or July and go far in Chiloé Island in September or October, to spend the next several months there and return north in April. The self-sufficient chicks brand their maiden migration from Alaska a bit later at the end of July, flying to central Canada on their own, without adult supervision. They may make other portions of their first migration unassisted; it'due south not notwithstanding known. How they are able to exercise that is another shorebird mystery. A Hudsonian godwit lives about 10 to 12 years. These new hatchlings will brand the global crossing every bit many as 24 times.

The data gathered here and on the Chilean finish will help fill out the unknowns of this bird, and also, researchers promise, offer assistance to a species in decline. Currently there are fewer than lxx,000 Hudsonian godwits. The population in Manitoba has fallen some three.5 percent annually. The Alaska population may also be declining. The bar-tailed godwit population has declined as well in recent years. A big function of the piece of work is answering why.

What Senner is doing here is existence replicated in many places. Researchers in Asia, Africa, Europe and the Americas are working in their corners with partners on the other ends of the world. Facing similar issues, they promise to fill in the pieces of the migratory bird puzzle and come up up with conservation strategies.

Because these birds travel such long distances to a wide variety of places and many of the bug they face are unknown, there is a long list of disparate challenges. A main culprit in the decline of the Manitoba population of Hudsonian godwits, for instance, is a irresolute climate that has altered weather patterns and created a mismatch between the time the godwit babies hatch and superlative insect affluence. Now, when the chicks emerge from their shells, the bugs are mostly gone, making them susceptible to starvation. The bugs are still plentiful when they hatch here in Alaska, but if their numbers are failing, it may take something to do with their single stopover en road, in the ephemeral wetlands of the central U.S. Precipitation patterns and farming practices are changing, and ponds may be drying up. Senner'due south PhD student, Jennifer Linscott, is studying that at present.

"Birds aren't falling out of the sky," says Senner, "So what is information technology? I call back the problems are compounding. They don't gain plenty weight before they leave, they hit caput winds, h2o isn't where they found it before, and they arrive in Alaska and it's warmer than expected. That'south how these declines are happening."

"Civilization is built on the continuance of climate. Listen to the birds for God'south sake and they will tell us what is going on."

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/46/8f/468fcd4f-5a0b-4e8f-b22a-b36e3a8b314d/janfeb2022_d05_migratorybirds.jpg)

In 2014 Senner started corresponding with Juan G. Navedo, a Spanish biologist who works with a team of students and biologists in Chile. "Tourism is i of the main threats to godwits outside of their breeding areas," says Navedo, who heads the Bird Environmental Lab at the Universidad Austral de Chile with back up from the Chilean National Science and Technology Research Fund. "There is a lot of shoreline development. It's a large, big problem." Hunters kill the birds, feral and domestic dogs chase them, people build shanties in their feeding grounds, locals gather red algae with ox carts and tractors to provide agar for the manufacture of cosmetics and pharmaceuticals, and piles of trash add to the constellation of threats. With fiscal back up from the Packard Foundation and the National Audubon Society, Chile's Center for the Written report and Conservation of Natural Heritage secured an important roosting site on Chiloé Isle.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/79/26/7926362e-ed57-489e-a5d9-48ed9a314b23/janfeb2022_d02_migratorybirds.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/77/b0/77b0dc42-908e-419c-8bfb-da39d0e5ec26/janfeb2022_d04_migratorybirds.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/bc/d6/bcd6f4f7-2cf7-4241-8a85-fec25459b9a9/janfeb2022_d03_migratorybirds.jpg)

Navedo is also concerned about the chemicals and antibiotics that launder ashore from massive salmon-rearing pens in the Gulf of Ancud. The toxins become absorbed into the sediment, and the birds who alive there comport high levels of antibiotic-resistant leaner, probably ingesting information technology from the worms they eat. Navedo and his students bandage cannon nets over the birds and catch xxx to twoscore of them at a fourth dimension to sample their gut microbiota.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/7d/55/7d550a0f-49a7-48fa-a7ca-ff559320e32c/janfeb2022_d10_migratorybirds.jpg)

Back on the bog at Beluga, Alaska, there are no concerns nigh crowds of people. The researchers are the just ones visible in the vast, empty landscape. A Hudsonian godwit mama roosts at the top of a blackness spruce, watching over Senner as he goes nearly his business concern with her babies.

My time here with the godwits is helping me realize that what we see in these magnificent creatures is not simply a bird, merely the incredible result of the millions of years of sculpting and tweaking by evolutionary pressures. That makes their turn down even more poignant, and ominous. "I see them more and more equally the Romans did, as augurs, with everything that is happening," says Piersma. "Civilization is built on the continuance of climate. Heed to the birds for God's sake and they volition tell united states of america what is going on."

Source: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/hudsonian-godwit-flies-thousands-miles-without-resting-180979248/

Posted by: flemingyourejough.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Animal Can Run The Longest Distance Without Stopping"

Post a Comment